Last week was an intensely bored Upper Ordovician bryozoan, so it seems only fair to have a thoroughly encrusted Upper Ordovician brachiopod next. The above is, although you would hardly know it, the ventral valve exterior of a common strophomenid Rafinesquina ponderosa from the Whitewater Formation exposed just south of Richmond, Indiana (locality C/W-148). I collected it earlier this month on a trip with Coleman Fitch (’15).

Last week was an intensely bored Upper Ordovician bryozoan, so it seems only fair to have a thoroughly encrusted Upper Ordovician brachiopod next. The above is, although you would hardly know it, the ventral valve exterior of a common strophomenid Rafinesquina ponderosa from the Whitewater Formation exposed just south of Richmond, Indiana (locality C/W-148). I collected it earlier this month on a trip with Coleman Fitch (’15).

This is the other side of the specimen. We are looking at the dorsal valve exterior. Enough of the brachiopod shows through the encrusters that we can identify it. Note that both valves are in place, so we say this brachiopod is articulated. Usually after death brachiopod valves become disarticulated, so the articulation here may indicate that the organism had been quickly buried. This brachiopod is concavo-convex, meaning that the exterior of the dorsal valve is concave and the exterior of the ventral valve is convex.

This is the other side of the specimen. We are looking at the dorsal valve exterior. Enough of the brachiopod shows through the encrusters that we can identify it. Note that both valves are in place, so we say this brachiopod is articulated. Usually after death brachiopod valves become disarticulated, so the articulation here may indicate that the organism had been quickly buried. This brachiopod is concavo-convex, meaning that the exterior of the dorsal valve is concave and the exterior of the ventral valve is convex.

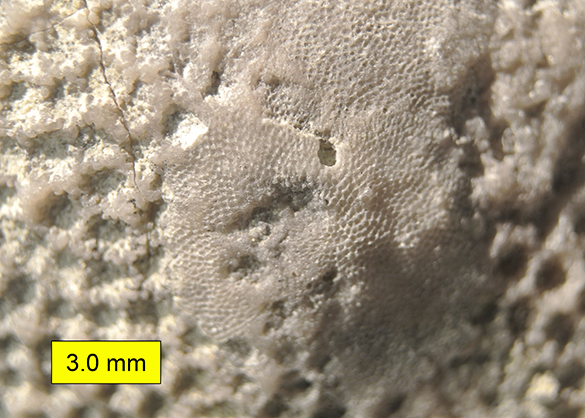

Returning to the ventral valve, this is a close-up of the encruster that takes up its entire exterior surface. It is the colonial heliolitid coral Protaraea richmondensis Foerste, 1909. (Note the species name and that it was collected just outside Richmond, Indiana.) This thin coral is a common encruster in the Upper Ordovician. Usually it is a smaller patch on a shell. This is the most developed I’ve seen the species. The holes, called corallites, held the individual polyps.

Returning to the ventral valve, this is a close-up of the encruster that takes up its entire exterior surface. It is the colonial heliolitid coral Protaraea richmondensis Foerste, 1909. (Note the species name and that it was collected just outside Richmond, Indiana.) This thin coral is a common encruster in the Upper Ordovician. Usually it is a smaller patch on a shell. This is the most developed I’ve seen the species. The holes, called corallites, held the individual polyps.

The encrusting coral has an encruster on top of it. This is a trepostome bryozoan, which you can identify by the tiny little holes (zooecia) that held the individuals (zooids). The patch of coral it is occupying must have been dead when the bryozoan larva landed and began to bud.

The encrusting coral has an encruster on top of it. This is a trepostome bryozoan, which you can identify by the tiny little holes (zooecia) that held the individuals (zooids). The patch of coral it is occupying must have been dead when the bryozoan larva landed and began to bud.

Now we’re returning to the concave dorsal valve with its very different set of encrusters. This is a close-up of another kind of trepostome bryozoan, this one with protruding bumps called monticules. They may have functioned as “exhalant current chimneys”, meaning that they may have helped channel feeding currents away from the surface after they passed through the tentacular lophophores of the bryozoan zooids. For our purposes, this is a feature that distinguishes this bryozoan species from the one on the ventral valve.

Now we’re returning to the concave dorsal valve with its very different set of encrusters. This is a close-up of another kind of trepostome bryozoan, this one with protruding bumps called monticules. They may have functioned as “exhalant current chimneys”, meaning that they may have helped channel feeding currents away from the surface after they passed through the tentacular lophophores of the bryozoan zooids. For our purposes, this is a feature that distinguishes this bryozoan species from the one on the ventral valve.

There is a third, very different bryozoan on the dorsal valve. This blobby, ramifying form is a well-developed specimen of Cuffeyella arachnoidea (Hall, 1847). It is again a common encruster in the Upper Ordovician, but not usually so thick.

There is a third, very different bryozoan on the dorsal valve. This blobby, ramifying form is a well-developed specimen of Cuffeyella arachnoidea (Hall, 1847). It is again a common encruster in the Upper Ordovician, but not usually so thick.

If we look closely at the hinge of the brachiopod on the dorsal side, we can see a much smaller C. arachnoidea spreading on the ventral valve.

If we look closely at the hinge of the brachiopod on the dorsal side, we can see a much smaller C. arachnoidea spreading on the ventral valve.

Finally, this is a side view of the brachiopod with the ventral valve above and the dorsal valve below. We’re looking at the junction of the articulated valves, the commissure. For the entire extent of the commissure, the encrusting coral grows to the edge of the ventral valve and no further. This is a strong indication that the brachiopod was alive when the coral was growing on it. The brachiopod needed to keep that margin clear for its own feeding.

Finally, this is a side view of the brachiopod with the ventral valve above and the dorsal valve below. We’re looking at the junction of the articulated valves, the commissure. For the entire extent of the commissure, the encrusting coral grows to the edge of the ventral valve and no further. This is a strong indication that the brachiopod was alive when the coral was growing on it. The brachiopod needed to keep that margin clear for its own feeding.

The paleoecological implications here are that the coral was alive at the same time as the brachiopod. This means that the convex exterior surface of the ventral valve was upwards for the living brachiopod. The concave exterior surface of the dorsal valve faced downwards. The coral and bryozoan encrusting the top of the living brachiopod were exposed to the open sea; the bryozoans encrusting the undersurface of the living brachiopod were encrusting a cryptic space. We are thus likely seeing the living relationships between the encrusters and the brachiopod — this encrustation took place during the life of the brachiopod.

Further, this demonstrates that this concavo-convex strophomenid brachiopod was living with the convex side up. This has been a controversy for decades in the rarefied world of brachiopod paleoecology. This tiny bit of evidence, combined with some thorough recent studies (see Dattilo et al., 2009; Plotnick et al., 2013), strengthens the case for a convex-up orientation. Back when I was a student these would be fighting words!

References:

Alexander, R.R. and Scharpf, C.D. 1990. Epizoans on Late Ordovician brachiopods from southeastern Indiana. Historical Biology 4: 179-202.

Dattilo, B.F., Meyer, D.L., Dewing, K. and Gaynor, M.R. 2009. Escape traces associated with Rafinesquina alternata, an Upper Ordovician strophomenid brachiopod from the Cincinnati Arch Region. Palaios 24: 578-590.

Foerste, A.F. 1909. Preliminary notes on Cincinnatian fossils. Denison University, Scientific Laboratories, Bulletin 14: 208-231.

Mõtus, M.-A. and Zaika, Y. 2012. The oldest heliolitids from the early Katian of the East Baltic region. GFF 134: 225-234.

Ospanova, N.K. 2010. Remarks on the classification system of the Heliolitida. Palaeoworld 19: 268–277.

Plotnick, R.E., Dattilo, B.F., Piquard, D., Bauer, J. and Corrie, J. 2013. The orientation of strophomenid brachiopods on soft substrates. Journal of Paleontology 87: 818-825.